By Kamal U Din, MA History

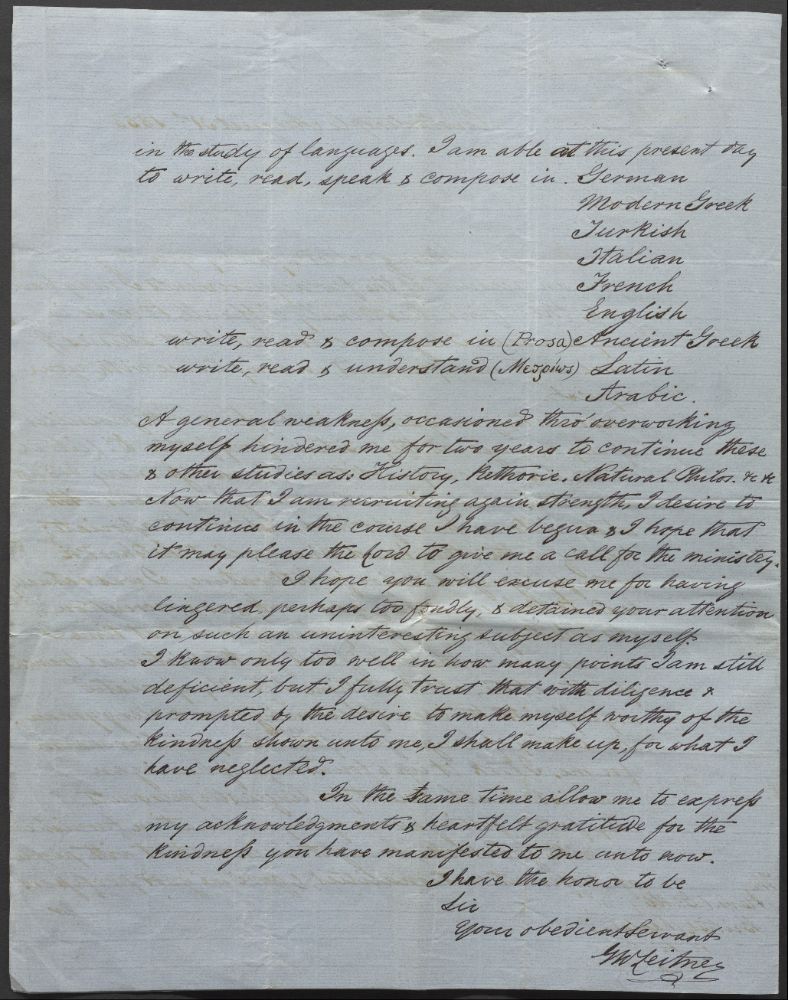

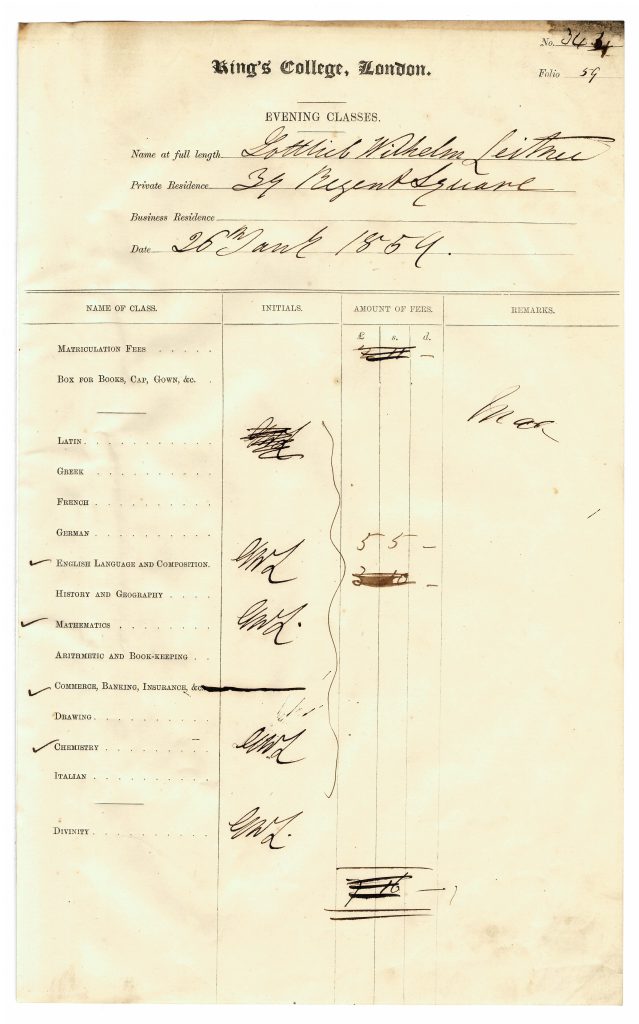

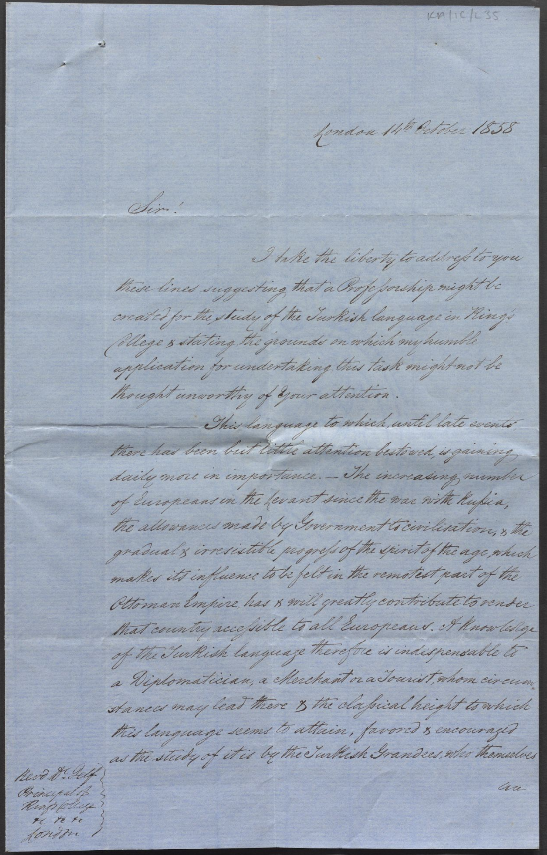

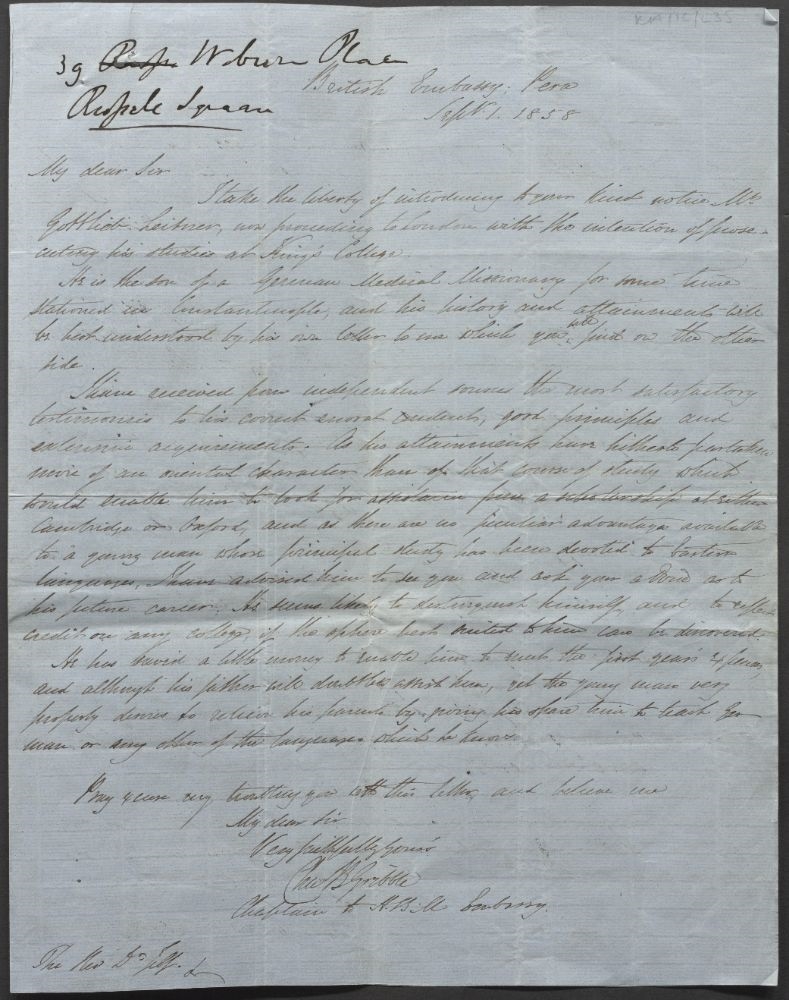

In a letter to the British Embassy Chaplain dated 31st August 1858, Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner stated that he knew eight languages including Italian, German, French, Ancient and Modern Greek, Arabic and Turkish. These linguistic skills, combined with his multicultural and multi-faith background; his stay in the Ottoman Empire; his work as an educator in India; his travel to the almost unknown region between Kashmir and Afghanistan; and his authorship of five books on the region now known as Gilgit Baltistan, make him one of the most interesting figures of Victorian Age. However, he is one of the least known Orientalists of his time. Therefore, this article discusses several aspects of Leitner, focusing on the context of his correspondence with King’s College, requesting them to appoint a Chair for Turkish and Greek languages. This correspondence with King’s College dates from August 31st to December 7th, 1858 when he was eighteen years old.

Dr Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner, an educationist and orientalist, was born on 15th September 1840 in Pest, Hungary into a Jewish family, and it is now understood that he later became a Jewish Christian. Leitner’s name is registered at the Jewish community records as Gottlieb Sapier. His biological father, Leopold Sapier, was a woollen merchant and the elder brother of Moritz Gottlieb Saphir, a well-known linguist and editor and also of Israel Saphir, whose son Adolph Saphir became a renowned Presbyterian minister and Protestant theologian in London. This shows his multi-faith and multicultural family background. Leopold Sapier died in 1845 and Leitner’s mother likely left Hungary because of the Hungarian Revolution of 1845 and moved to Constantinople with Leitner and his sister. There she met her second husband Dr Johann Moritz Leitner, who is often mistakenly regarded as Leitner’s biological father as Gottlieb even adopted his stepfather’s surname. Johann Leitner was also a convert from Judaism to Protestantism and was a missionary doctor probably in Palestine to convert Jews to Protestantism. In 1861, in his petition for British naturalisation, Gottlieb declared himself an Anglican. However, his religious affiliations always remained ambiguous as his name appeared in Jewish records and newspapers, he later converted to Christianity, joined a Muslim religious seminary in the Ottoman Empire and learnt medieval Muslim philosophy from Muslim clergy, primarily focusing on Maimonides—a medieval Jewish philosopher in Muslim Spain.

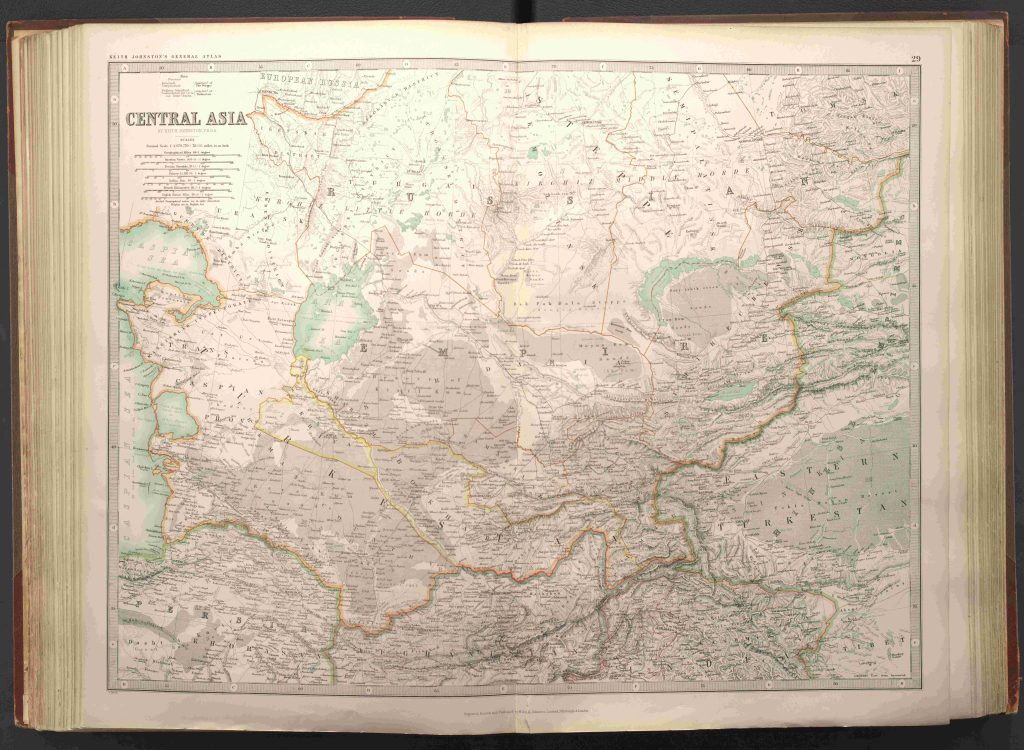

Leitner, in his Lecture on the Races of Turkey, states that being a Christian he succeeded to gain admission to an Islamic school in Constantinople, due to his stepfather’s influence and reputation.[1] There, Leitner studied Islamic culture and scholarship deeply, eventually attending the ‘Muhammadan Theological School’ in 1856, likely either the Sahn-ı Seman Medrese or possibly the Caferaga Medrese. He became proficient in Arabic, memorised extensive portions of the Quran and adopted the Arabic name Abdur Rasheed Sayyah (‘Sayyah’ meaning ‘traveler’). During his travels in 1886 through Dardistan, the region between Oxus and Indus rivers, he disguised himself as a Bokhara Mullah. Interestingly, part of his Islamic education including studying the medieval thought, shaped by Islamic and Greek traditions, remains part of the curriculum in Islamic colleges in Istanbul today. This period of study left a lasting impact on Leitner and likely deepened his affinity for Islam.[2]

At the time when his correspondence began with King’s College in the mid-nineteenth century, major European engagement with the East especially with Arabic and Hebrew text had declined as a lot had been written since the dawn of Modernity from the Renaissance and Reformation to the Enlightenment. As a result, there was an increasing interest among the Orientalists towards other Eastern societies and their languages such as Persia, India and China. Numerous Chairs were established for Eastern languages in Western universities especially for Arabic and Hebrew from sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, likewise, by the beginning of the nineteenth century several Chairs for languages other than Arabic and Hebrew were established throughout the Western universities.[3]

In the College de France, a Persian chair was established in 1806 and a chair of Sanskrit in 1815. However, England initially did not take part in the competition until 1833 when a chair of Sanskrit was established at Oxford, followed by Cambridge and Edinburgh universities. Therefore, Leitner, a young Orientalist who already knew several languages and had spent his youth in the Ottoman Empire, learning Islamic studies in various schools, sought to begin a career in Oriental studies. For this purpose, he preferred King’s College, writing multiple letters from Turkey and showing his interest to teach Turkish or Greek or the other dozens of languages he claimed to already know. However, the question arises why he preferred King’s college over other British or European universities. The answer can be found in one of the letters in correspondence with Kings College.

In a letter to King’s College London, the British Embassy Chaplain in Pera, Turkey (whom Leitner had previously informed about his plans in a letter dated 31 August 1858) informed the Principal of the college about Leitner’s intentions to begin a career in Oriental studies, especially Oriental languages. In the letter, he stated that Leitner was fully versed in Oriental languages and needed some guidance and advice. He stated that he initially intended to seek guidance from Cambridge or Oxford but there was no space for such a young man and mentioned that he suggested Leitner should seek help from the Principal of King’s College.[4] It answers the question that is why King’s College, and not any other institution in the UK. It’s because there were already chairs and professors at other universities like Cambridge and Oxford.

The letters not only depict the shift in Oriental discourse in the European context but they also reveal a lot about European interest in their colonies especially in the context of Orient or the East. The European expansion and the formal colonisation of the East at the beginning of the nineteenth century is deeply connected with body of Eastern knowledge held by the Europeans. The major critique of the Oriental or colonial studies of non-Europeans were challenged during the latter half of the twentieth century both in the Western and Eastern contexts. In the West, figures like Foucault and Derrida challenged the existing epistemologies and social structures, creating powerful tools to critique European dominance, both political and epistemological. Figures like Edward Said applied such tools to Oriental discourse, considering it inherently biased towards Eastern societies.[5]

When these discussions are related with the letters, a strong connection can be observed. The letters in many ways echo the colonial interests and biases in the colonies. For instance, in one of the letters, Leitner, while mentioning the importance of the Turkish language, stated that the Europeans should learn Turkish language because it would be helpful in the Russo-Turkish conflict and particularly useful for the British during the conflict. Not only this, he states in the same letter that the Europeans’ need for translators and interpreters to communicate with local authorities means that secrecy is lost. Therefore, he advocates for the learning of Turkish language so Europeans could directly negotiate with the local authorities. The third point which Leitner discussed is also related to the colonial interests. While writing to the Principal of King’s College London, he emphasised that learning Eastern languages would expedite the civilising process as the word of the Gospel had not reached most parts of the Ottoman Empire. It illustrates the dominant perception that the Europeans considered the colonised people less civilised, recommending that they should be civilised by giving them the word of the Gospel and values of Western civilisation.

However, it is quite evident that Leitner’s ideas changed over time as he spent more time in King’s College London and later became Principal of Government College Lahore, British India. Leitner’s correspondence with King’s College London can be related to the imperial educational system of colonies which he became part of, in 1864 establishing several educational institutions and writing about the importance of indigenous education in native languages in India. Leitner was keen to work with Oriental languages especially those that had been neglected. This idea can be related to the major debate of the nineteenth century on the nature of education in British colonies, especially in India. This debate is primarily known as the controversy between the Anglicists and Orientalists. The Anglicists[6] advocated English-language education, incorporating Western knowledge and literature as part of the curriculum. It meant that Indians who studied Vedic lore, astrology, the Upanishads, the Quran or Persian poetry would be exposed to the western curriculum and the works of European thinkers like Newton, Locke and Bacon.[7] On the other hand, the Orientalists strongly opposed this stance, supporting the continuation of education in Eastern or vernacular languages. They argued that introducing European languages and an English-based curriculum would alienate the indigenous population and ultimately provoke resistance against British colonial rule.[8]

To resolve the conflict between European and Oriental education, the East India Company issued educational dispatches in 1841 and 1854. The 1841 dispatch suggested maintaining a balance but emphasised that the purpose of education should be to spread European knowledge in vernacular languages under European supervision.[9] The 1854 dispatch took a more balanced position, praising both Western and Eastern knowledge. It proposed a system where Oriental knowledge in vernacular languages would be taught at lower levels, while English and Western sciences would be part of higher education, though the central purpose of the curriculum still remained the dissemination of Western knowledge and science in vernacular languages.[10]

The British Indian administration sought to create institutions aligned with its educational goals to spread Western knowledge and sciences in vernacular languages as well as the traditional education, leading to the founding of Government College Lahore in 1864 with Leitner as its first principal. He later played a key role in founding the University of Punjab in 1882, offering both Oriental and English language education. In History of Indigenous Education in the Panjab, Leitner praised the East’s deep respect for learning and critiqued British educational policies for neglecting vernacular traditions. Advocating a blended system, he proposed local languages for early education and English for higher studies.[11]

Reflective Account

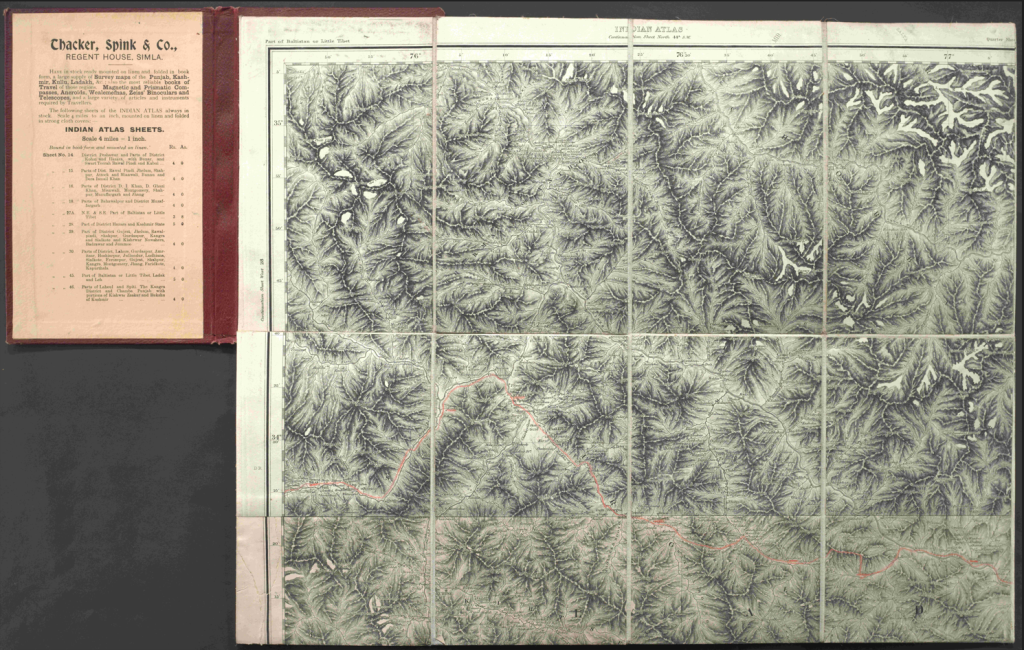

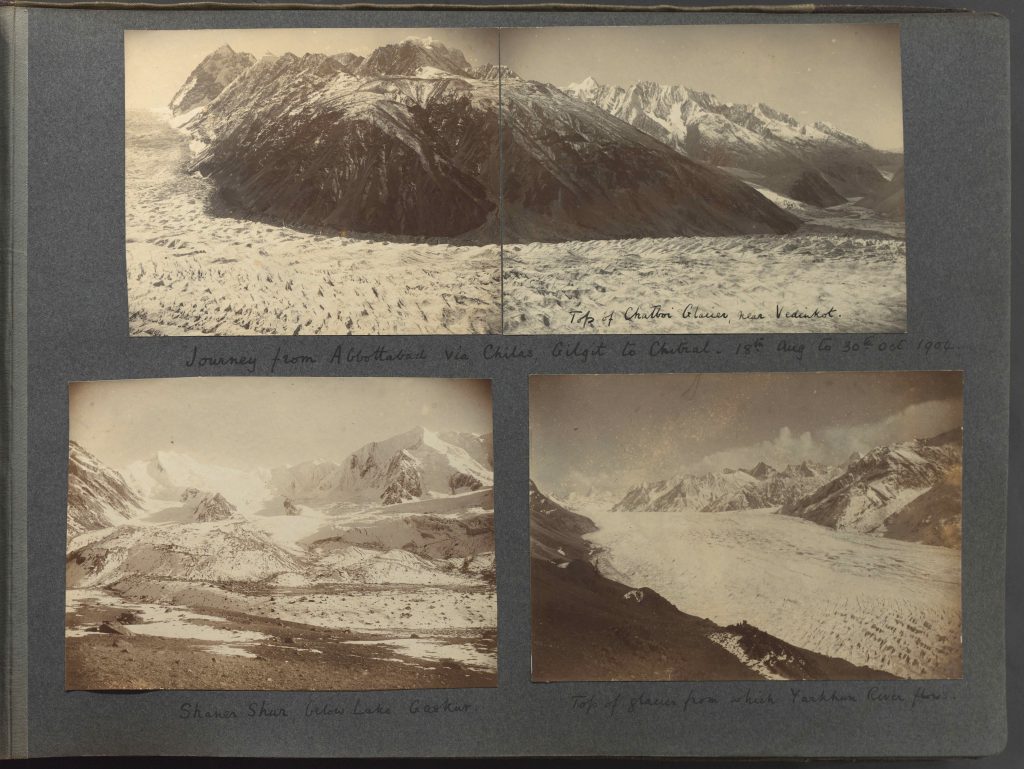

The internship provided me with opportunities to learn in many ways. It gave me profound insights into Orientalism, colonial philological studies, colonial education and importantly the historical background of the universities like King’s College London, Government College University Lahore and Punjab University Lahore. In addition, it also provided me with practical skills related to archives as well as team work.[12] Furthermore, this project interested me because I learned during the first meeting that I would be working on the letters of Leitner, whom I had already heard about repeatedly back at home in every family gathering, at the dining table and in my friends’ circle because Leitner was the first European who crossed the Indus River in Gilgit Baltistan to explore the region between Oxus and Indus rivers. The region was isolated, being a hard, mountainous area distant from cultural centers. Leitner did remarkable work on the languages, culture, norms and rituals of the region, writing five books on Gilgit Baltistan.

However, my task was related to his correspondence with King’s College London. On the first day, the archive team, Clare and Kate, briefed me about the project and encouraged me to plan it in the way I preferred. I began the project by finding the necessary material Leitner wrote before and during his stay at King’s College London. Clare and Kate also provided advice and help at every stage, even in finding the material. I finally selected four letters: two of them written by Leitner himself to King’s College London, requesting to open a professorship for Turkish and Greek languages, one to the British Embassy Chaplain, informing about his plans and one written by the Chaplain of British Embassy in Turkey to King’s College, informing them about Leitner’s intentions.

Initially, I found it difficult to read the letters, but after trying multiple times, I became familiar with the writing style, identifying how he writes or crafts a letter. Still, there were words that I could not transcribe, so I put ellipses in place of those words. I generally found Leitner’s handwriting quite easy to understand. However, I struggled to transcribe the letter written by the British Embassy Chaplain in Pera to King’s College which served as a reference letter for Leitner’s admission. For that letter, I asked for help from the archive team and received Gemma’s assistance. It was a three-hour long session where Gemma and I went through the letters word by word, analysing every letter. Gemma not only helped me read the difficult words but also cross-checked the transcriptions against the original manuscripts to ensure there were no errors. It was really helpful for me, as I got a chance not only to read a letter or word but also to discuss it with members of the archive team.

One example was quite interesting: when Gemma and I finished proofreading, we could not understand one word even after attempting many times. Then Gemma said that our eyes might be tired and unable to recognise the word, so it would be best to ask someone else. She then asked Manuela, who, after looking at the word, said it’s ‘relieve,’ which was correct. Gemma said when we focus on a word for a long time, it becomes difficult to recognise it, so one needs to divert their eyes and return, which I found amusing.

The second challenging part was reading the words or short descriptions at the corners and sometimes at the bottom of the page. For that, I transcribed what I understood, mostly names and designations of people. Then I searched for those names and places where they lived, just to have a clear idea, but for the words that I did not understand, I put dots (…) in their place. After the transcription, I started working on the blog post and exhibition. For that purpose, with the help of Clare and Kate, I began searching for maps and pictures related to Leitner’s expedition to different parts of India. The purpose was to create a clear picture of his life and work. During this time, I found some rare, unpublished pictures of the mountainous region of Gilgit Baltistan, Kashmir, Tibet and Ladakh, which he visited in 1866. In addition, there were one or two other archives related to his stay in India.

The internship also impacted my academic and intellectual growth. I am interested in cultural and intellectual interactions between different cultures in Early Modern period and currently working on how the Early Modern accounts depicted the non-European cultures for my final dissertation. Therefore, this internship provided me with opportunity to access archival material and analyse it. I problematise the idea that Oriental discourse is inherently biased and partial as an outcome of western thought system, arguing that sources should be evaluated individually to break the constructed narratives. By reading Leitner’s letters and his other works, I concluded that the Oriental discourse is a complex phenomenon and it is difficult to take a definitive position supporting or opposing the discourse.

This complexity became especially apparent when examining Leitner’s evolving position from the time he corresponded with King’s College London to his work for education in India. In the letters, he was clearly serving the colonial interests like he mentioned the civilising project and stated the need to keep secrets. On the other hand, during his stay in Punjab British India, he strongly criticised the colonial efforts in education. He clearly states that the Western educational system has damaged the indigenous educational systems and given a poor educational system which is not functional at the ground level. In this way, this project helped to structure my dissertation in a better way. It also supports the argument of the dissertation that the Oriental discourse is a complex corpus of literature sometime biased or exoticising and sometimes neutral.

In conclusion, the internship was a journey of learning, both theoretically and practically. Theoretically, it provided a thorough understanding of the late nineteenth-century developments in Oriental discourse and the role of Western universities in shaping it. Practically, it provided me with the necessary tools and skills to work with archives, including accessing and analyzing manuscripts. The selected letters, along with other works of Leitner, not only show how nineteenth-century colonial powers utilised Oriental discourse to justify and strengthen their rule in Eastern societies, but also reveal how colonial authorities sought to learn Eastern languages in order to better understand the societies they frequently interacted with. This further reflects the colonial interest in dominating other nations while developing ideological and academic justifications for their rule. Studying multiple cultures and societies remains essential in today’s multicultural and globalised world. After the transatlantic slave trade (sixteenth to nineteenth century), Western countries have witnessed mass migration in recent decades, particularly from Asian nations which continues to shape Western societies in various ways. Therefore, incorporating the norms, values, and internal diversities of Eastern societies into academic discussions can develop mutual understanding, promote peace, and help prevent conflicts in future.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources

Leitner, Gottlieb Wilhelm. Correspondence with King’s College London, August–December 1858. KA/IC/L35. King’s College London Archives.

Leitner, Gottlieb Wilhelm. Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being an Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial), Darel, Tangir, and of Some Parts of the Hindukush in Gilgit Mission and the Hunza-Nagar Political Agency. Woking: Oriental Printing and Publishing House, 1893.

———. The Hunza and Nagyr Handbook: Being an Introduction to a Knowledge of the Language. Calcutta: Government Printing, 1889.

———. History of Indigenous Education in the Panjab since Annexation and in 1882. Lahore: Government Civil Secretariat Press, 1882.

———. Results of a Tour in Dardistan, Kashmir, Little Tibet, Ladakh, Zanskar, etc. Lahore: Government Civil Secretariat Press, 1877.

———. A Vocabulary of the Shina Language (as Spoken by the Minaro in Gilgit). Lahore: Punjab Government Press, 1881.

Macaulay, Thomas Babington. “Macaulay’s Minute on Education, February 2, 1835.” In Selections from Educational Records, Part I (1781–1839), 107–117. Bureau of Education, India. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, 1891.

The General Council on Education in India. The Despatch of 1854 on “General Education in India.” London: General Council on Education in India, 1854.

Bureau of Education, India. Selections from Educational Records, Part II (1840–1859). Edited by J. A. Richey. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, 1922.

Secondary Sources

Bevilacqua, Alexander. The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Evans, Stephen. “Macaulay’s Minute Revisited: Colonial Language Policy in Nineteenth-century India.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23, no. 4 (2002): 260–281.

Harlow, Barbara, and Mia Carter, eds. Archives of Empire, Vol. I: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Viswanathan, Gauri. Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

[1] G. W. Leitner, A Lecture on the Races of Turkey (Both of Europe and Asia), and the State of Their Education: Being, Principally, a Contribution to Muhammadan Education (Lahore: Indian Public Opinion Press, 1871), 16.

[2] History. International Dr G. W. Leitner Trail. JTrails: The National Anglo-Jewish Heritage Trail.

[3] Barbara Harlow and Mia Carter, eds., Archives of Empire, Vol. I: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003).

[4] Gribble Chaplain to British Embassy, Pera Ottoman Empire to the Principal King’s College London dated September 1, 1858.

[5] Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York, 1978), Introduction.

[6] The Anglicism heavily relied on Oriental discourse to support their argument. Orientalist scholarship, which produced corpus of knowledge about Eastern societies, provided Anglicists with the basis to critique and compare cultures. Viswanathan’s argument shows that the Orientalism were instrumentalised by the colonial authorities to gain their interests in the colonies. See, Gauri Viswanathan, Masks of Conquest: Literary Study and British Rule in India (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), 30–45.

[7] Hayden J. A. Bellenoit, Missionary Education and Empire in Late Colonial India, 1860–1920 (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007), 1–12.

[8] Viswanathan, Masks of Conquest: 30–45.

[9] Bureau of Education, India, Selections from Educational Records, Part II (1840–1859), ed. J. A. Richey (Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, 1922), 4.

[10] The Despatch of 1854 on “General Education in India,” reprinted by the General Council on Education in India (London: 7 Adam Street, Strand, 1854), 5-15.

[11] Leitner, History of Indigenous Education in the Panjab since Annexation and in 1882, (Lahore: Government Civil Secretariat Press, 1882), p. i-iii.

[12] It was my first experience working with a diverse team as before I worked with my friends and previous colleagues as a volunteer.